Health

Six Key Recommendations for Improving Mental Healthcare in L.A.’s Thai Community

Mental healthcare for Los Angeles’ Thai community requires nuanced approaches tailored to cultural values and practical needs. Conversations with therapists, social workers, and researchers highlighted six key recommendations that can enhance treatment outcomes for Thai and Asian American individuals.

Addressing Practical Needs First

High dropout rates among Asian Americans in therapy have raised concerns about engagement. Dr. Gordon Hall, a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Oregon, emphasizes the importance of addressing practical issues before delving into emotional discussions. “Some therapists may spend the first three weeks on a client’s thoughts and feelings, but many Asian Americans might question the relevance of those discussions to tangible conflicts,” he noted.

At the Asian Pacific Counseling & Treatment Centers, case manager Natyra Na Takuathung collaborates with psychiatric social worker Wanda Pathomrit to assist clients, particularly Thai immigrants, in navigating social benefits. Pathomrit integrates case management into therapy, recognizing that many clients struggle with mental health issues and maintaining relationships with case managers. “By coaching in the moment, I help clients grow confidence and self-esteem while accessing services,” Pathomrit explained.

Despite the benefits of such programs, Na Takuathung noted that some clients hesitate to accept assistance, fearing they may be seen as “burdens” on society. She encourages them to embrace available resources, stating, “You deserve kindness. You’ve contributed to this country too.”

Involving Family in Care

Research shows that many Western therapeutic approaches emphasize individualism, which may not resonate with those from collectivist cultures. Hall and co-author Janie Hong highlight that for individuals in Asian communities, wellness is often tied to family and group harmony. “If you have a problem, that implicates your whole group,” Hall explained.

Christina Shea, chief clinical officer of Richmond Area Multi-Services, has witnessed firsthand the value of including family members in treatment. “Working with one individual is not enough; that person is connected with the family,” Shea remarked.

Monk Phramaha Dusit Sawaengwong at Wat Thai of Los Angeles often mediates conflicts arising from differing expectations between immigrant parents and their children. He encourages parents to allow their children to explore various opportunities without imposing rigid expectations, saying, “Just let them learn.”

Including Community in Care

Support systems can extend beyond family. Danielle Ung, a counseling and health psychology assistant professor at Bastyr University, is looking into how Southeast Asian students have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. She encourages patients to identify supportive community structures, which can include friends, extended families, and local organizations.

At Wat Thai temple, volunteer teachers Pam Evagee and Ta Sanalak coordinate cultural programs to help bridge gaps between generations. They emphasize the importance of understanding both traditional customs and the influence of American culture on children’s beliefs. “We understand the parent because we are Thai, and we understand the kid because we’ve lived here for quite some time,” Sanalak said.

The temple also provides an environment where children can connect with peers facing similar challenges, while parents often collaborate in meal preparation and share advice on family dynamics.

Practicing Mindfulness in a Community Context

Mindfulness, a core tenet of Buddhism, plays a significant role in mental health among Thai Americans. According to Hall, while Western therapies frequently incorporate mindfulness, they often focus on the individual. “Eastern-based mindfulness practices recognize the self within a community,” he explained.

Buddhist monk Phiphop Phuphong employs mindfulness techniques to support individuals like a diabetic man grappling with the emotional impact of losing a leg. Phuphong guided him through mindfulness exercises, helping him to find peace and strength for the sake of his family. “Your body is your present,” he advised.

Progress in Mental Health Policies and Training

The Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health is making strides to reach underserved communities through culturally competent services. Dr. Lisa Wong, who leads the department, acknowledged that while progress has been made, more work is needed to improve service delivery. “We’re trying to cover all of our bases, but I don’t think we’re going to make significant progress until we bring a more diverse workforce into mental health,” Wong stated.

Recruitment challenges persist, as many immigrants opt for higher-earning professions rather than entering mental health fields. Furthermore, executive director of the National Association of Social Workers’ California chapter, Carl Highshaw, pointed out that existing training often reflects predominantly Eurocentric models, which can overlook the complexities of immigrant and collectivist cultures.

“Cultural competence is not optional,” Highshaw asserted. He emphasized the need to move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach, advocating for interventions that honor cultural traditions and community networks.

The insights gathered from L.A.’s Thai community offer valuable perspectives that could enhance mental healthcare for diverse populations. As mental health professionals continue to adapt their practices, the focus on cultural context and community involvement may prove essential for fostering effective treatment strategies for all.

-

Top Stories1 month ago

Top Stories1 month agoRachel Campos-Duffy Exits FOX Noticias; Andrea Linares Steps In

-

Top Stories1 week ago

Top Stories1 week agoPiper Rockelle Shatters Record with $2.3M First Day on OnlyFans

-

Top Stories5 days ago

Top Stories5 days agoMeta’s 2026 AI Policy Sparks Outrage Over Privacy Concerns

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoLeon Goretzka Considers Barcelona Move as Transfer Window Approaches

-

Top Stories1 week ago

Top Stories1 week agoUrgent Update: Denver Fire Forces Mass Evacuations, 100+ Firefighters Battling Blaze

-

Top Stories1 week ago

Top Stories1 week agoOnlyFans Creator Lily Phillips Reconnects with Faith in Rebaptism

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days agoTom Brady Signals Disinterest in Alix Earle Over Privacy Concerns

-

Top Stories6 days ago

Top Stories6 days agoOregon Pilot and Three Niece Die in Arizona Helicopter Crash

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoTerry Bradshaw Updates Fans on Health After Absence from FOX NFL Sunday

-

Top Stories3 days ago

Top Stories3 days agoCBS Officially Renames Yellowstone Spin-off to Marshals

-

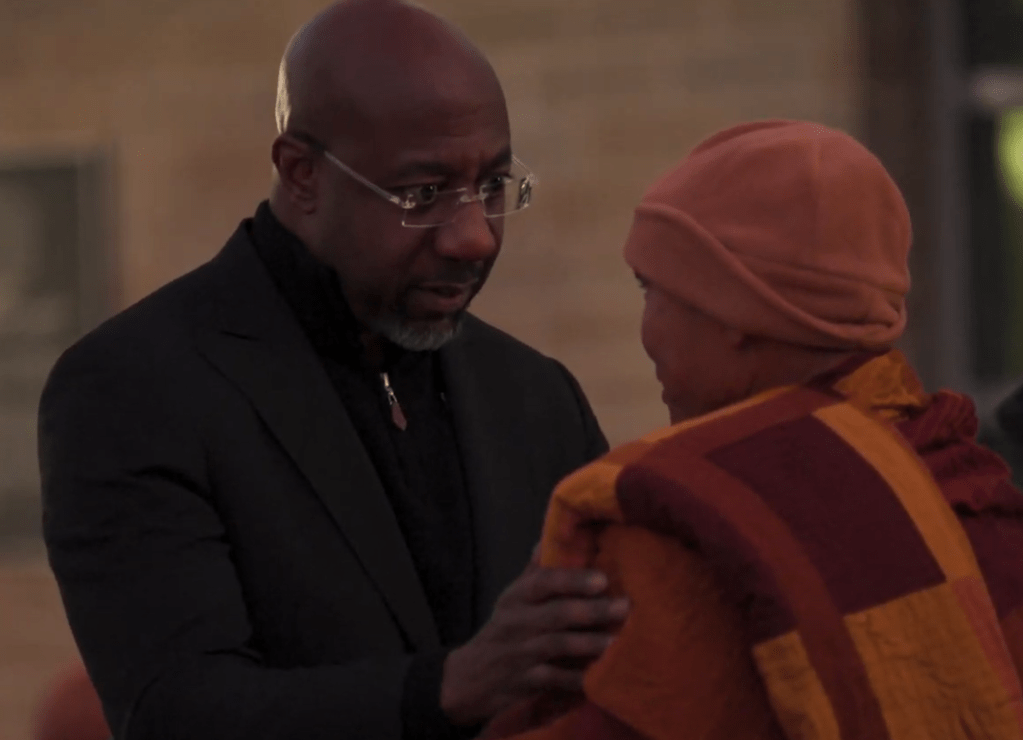

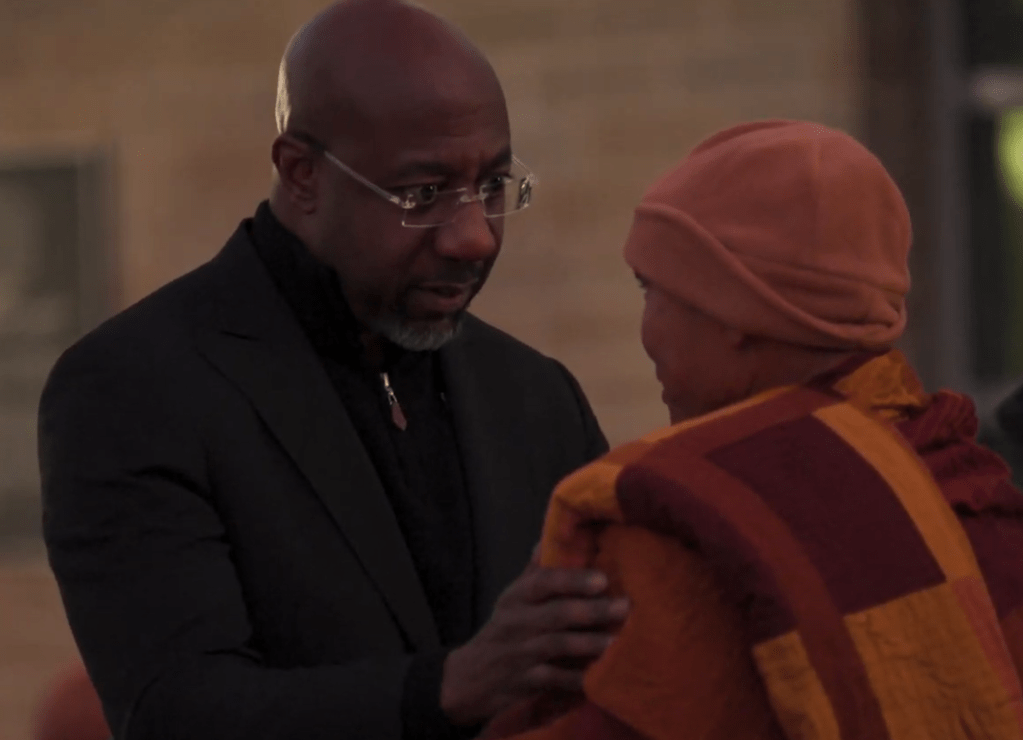

Top Stories5 days ago

Top Stories5 days agoWarnock Joins Buddhist Monks on Urgent 2,300-Mile Peace Walk

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSouth Carolina Faces Arkansas in Key Women’s Basketball Clash