Genetic Shifts Paved the Way for Upright Walking in Humans

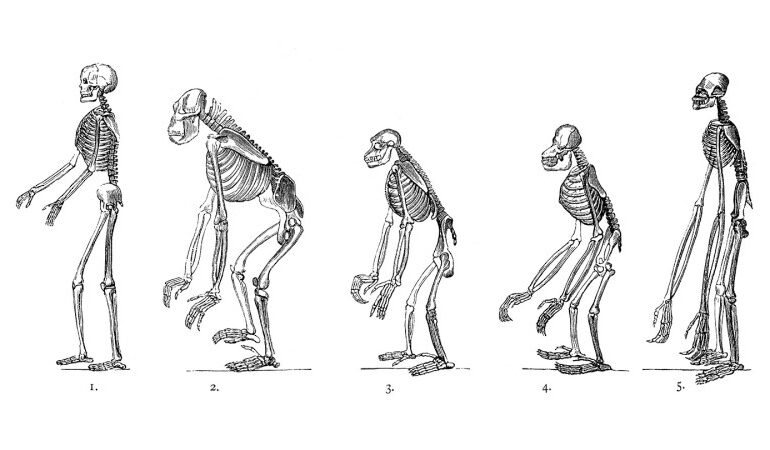

Research has identified two significant genetic changes that influenced the evolution of the human pelvis, enabling early ancestors to walk upright. The findings, published in the journal Nature on September 25, 2023, reveal how these shifts fundamentally altered pelvic structure, setting humans apart from other primates.

The first genetic alteration involved a 90-degree rotation of the ilium, a bone located in the pelvis. This rotation reoriented the muscles associated with the pelvis, effectively transforming the anatomical framework designed for climbing and running on four legs into one suited for bipedalism. The second change delayed the hardening of ilium cartilage into bone, allowing for a more gradual development of a distinctive bowl-shaped pelvis, which is essential for supporting an upright posture.

Researchers, including evolutionary biologist Gayani Senevirathne from Harvard University, documented these changes after examining microscopic slices of developing pelvic tissue from humans, chimpanzees, and mice. They combined their findings with CT imaging to reveal that human ilium cartilage grows sideways rather than vertically, as observed in other primates.

The slower transition of cartilage to bone compared to nonhuman primates contributes to the pelvis’s unique wide shape, crucial for stability when walking on two legs. The research indicates that specific biological on-off switches regulate the activity of genes responsible for cartilage and bone formation, leading to these evolutionary adaptations.

According to coauthor Terence Capellini, these genetic shifts were essential for repositioning the muscles from the back to the sides of the pelvis, which facilitates upright locomotion. The insights gained from this study reinforce a key principle in evolutionary developmental biology: significant anatomical changes often arise from subtle variations in gene activity timing and location, rather than the introduction of entirely new genes.

Carol Ward, an anthropologist at the University of Missouri, emphasizes the importance of these findings, noting that the ability to stand on one foot was critical for developing bipedal walking.

Interestingly, this research did not initially aim to explore human evolution. Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the scientists intended to investigate how the pelvis and knees develop to improve understanding of hip disorders. Capellini explained that their goal was to learn why the human pelvis differs from those of other primates and mice, particularly in relation to disease susceptibility.

Ironically, the anatomical changes that facilitated bipedalism may have also contributed to increased vulnerability to conditions such as osteoarthritis, which occurs more frequently in humans than in other primates. Capellini speculates that the wider hips resulting from these genetic adaptations might have also led to a more spacious birth canal, potentially allowing for the evolution of larger-brained offspring.

This research not only sheds light on our evolutionary past but also opens up avenues for future studies on human anatomy and health. By understanding the genetic underpinnings of our unique pelvic structure, scientists may better address related medical conditions and enhance knowledge about human development.