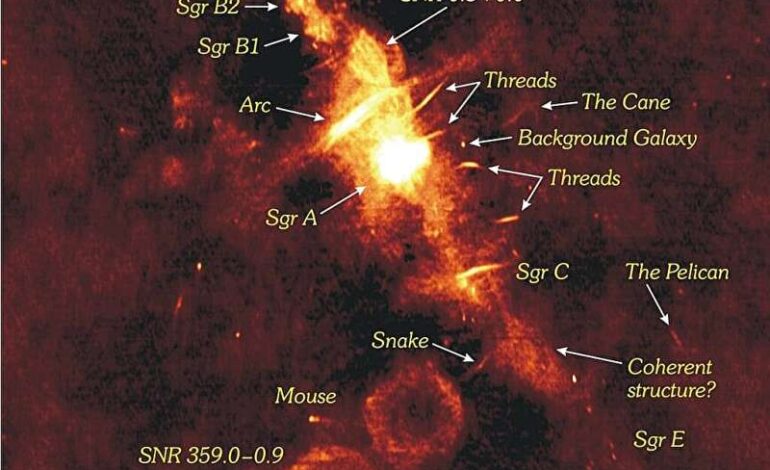

Astronomers Measure Satellite Radio Emissions from Space

Astronomers have conducted a groundbreaking study to measure radio emissions from satellites orbiting at an altitude of 36,000 kilometers. A research team from the CSIRO’s Astronomy and Space Science division has revealed that the majority of geostationary satellites do not emit unintended radio signals that could interfere with astronomical observations. This finding is crucial as it impacts the future operation of radio telescopes, particularly the upcoming Square Kilometer Array (SKA).

The research utilized archival data from the GLEAM-X survey, collected by the Murchison Widefield Array in Australia in 2020. The team focused on a frequency range of 72 to 231 megahertz, which is significant for low-frequency radio astronomy. By analyzing data from up to 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites over a single night, the researchers aimed to determine the presence of radio emissions.

The results were largely positive. Most of the satellites analyzed remained effectively invisible to radio telescopes within the studied frequency range. For the majority, the researchers established upper limits of less than 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power in a bandwidth of 30.72 megahertz, with the best results reaching an impressive 0.3 milliwatts. Only one satellite, Intelsat 10–02, showed potential unintended emissions at approximately 0.8 milliwatts, significantly lower than the emissions found in low Earth orbit satellites, which can emit hundreds of times that amount.

The significance of this study lies in the distance and geometry of geostationary satellites. Positioned ten times farther from Earth than the International Space Station, even strong emissions from these satellites diminish considerably by the time they reach ground-based telescopes. The study’s methodology involved pointing the telescope near the celestial equator, allowing each satellite to remain in view for extended periods. This strategy facilitated sensitive measurements that could detect even sporadic emissions.

As the Square Kilometer Array nears completion in Australia and South Africa, it promises to be far more sensitive than current instruments in the low-frequency range. While today’s telescopes might perceive certain emissions as background noise, future advancements could render such noise detrimental to their operations. The new measurements provide essential baseline data for predicting and mitigating potential radio frequency interference.

With an increasing number of satellite constellations being launched, the pristine radio environment that astronomers rely on is gradually diminishing. Even satellites designed to avoid specific protected frequencies can inadvertently emit signals through their electrical systems, solar panels, and onboard computers.

Currently, geostationary satellites appear to be maintaining a respectful presence in the low-frequency radio spectrum. However, as technology evolves and satellite traffic increases, the potential for interference remains a concern. The findings of this study, published on the arXiv preprint server, highlight the need for ongoing monitoring and research to safeguard the future of radio astronomy.

For further details, refer to the study by S. J. Tingay et al, “Limits on Unintended Radio Emission from Geostationary and Geosynchronous Satellites in the SKA-Low Frequency Range,” available on arXiv.