Scientists Convene to Address Ethics of Brain Organoid Research

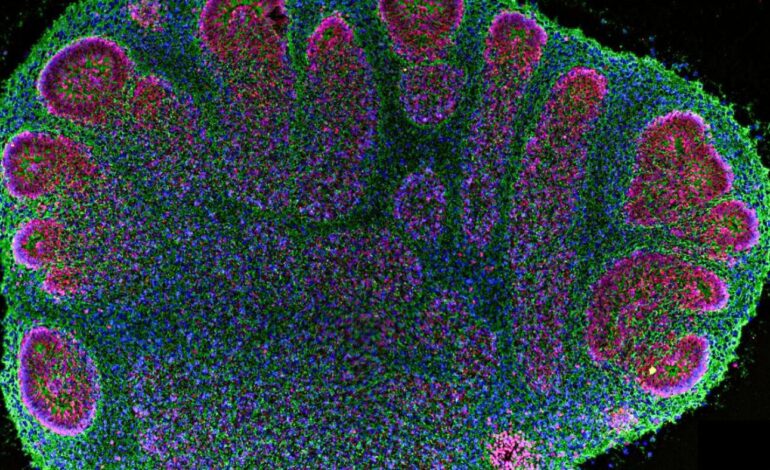

Research on brain organoids is transforming the landscape of neuroscience, but it also raises critical ethical questions. These small clusters of human cells model aspects of brain development and are increasingly used to study conditions such as autism, schizophrenia, and brain cancer. Recently, a diverse group of scientists, ethicists, patient advocates, and journalists gathered for two days at the Asilomar Conference Center on the Monterey Peninsula to discuss the implications of this innovative research.

Dr. Sergiu Pașca, a leading organoid researcher at Stanford University, hosted the meeting. His lab has utilized organoids to develop potential treatments for rare causes of autism and epilepsy. “For the first time, we have this ability to really work with human neurons and human glial cells,” Pașca explained. Despite the scientific advancements, he acknowledged that his work has sometimes sparked public unease, particularly when his team transplanted human organoids into the brains of rats.

As discussions unfolded, participants tackled several pressing questions: Is it ethical to place human organoids in animal brains? Can organoids experience pain or consciousness? Who should regulate this research? Bioethicist Insoo Hyun emphasized the need for caution. “We are talking about an organ that is at the seat of human consciousness. It’s the seat of personality and who we are,” he noted, advocating for careful consideration in experimental approaches.

The event’s format encouraged open dialogue among participants, allowing them to share diverse perspectives. Scientists and patient advocates often highlighted the urgency of finding cures and answers to complex neurological questions. In contrast, bioethicists stressed the importance of establishing guidelines to ensure informed consent and to avoid enhancing animal or human brains.

Participants recognized the need for transparency with the public regarding brain organoid research. Alta Charo, a professor emerita of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, pointed out the common public concern: “How far along are they in building organoids that can actually recapitulate something that we associate with human capacities?” While she reassured that the technology is not yet at that point, developments such as assembloids, which are networks of multiple organoids, are drawing closer to more complex brain-like structures.

Pașca’s team has notably constructed a network of four organoids to model pain signal pathways. Charo cautioned that this advancement might create misconceptions. “The mere existence of the pain pathway… is enough to give a public perception problem that the organoid or the assembloid is suffering,” she explained. Currently, these networks lack the circuitry necessary to feel pain, alleviating immediate ethical concerns. Nevertheless, she stressed the importance of proactive regulation and oversight to prevent future issues.

The media was also scrutinized for its portrayal of organoid research, often referring to them as “mini-brains.” This terminology has contributed to public misunderstandings, leading some to believe there are fully developed brains growing in laboratories. Dr. Guo-li Ming, an organoid researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, highlighted the necessity for scientists to clarify the actual capabilities and applications of organoids. Her lab is working on customizing brain cancer treatments using organoids derived from patients’ own tumor cells, showcasing the potential benefits of this research.

Concerns surrounding organoids echo previous societal debates regarding stem cell research. Over two decades ago, fears arose that neural stem cells could provide animals with human-like cognitive abilities. In contrast, organoids, which originate from stem cells, can thrive in animal brains and even integrate with their neural circuits, raising renewed ethical dilemmas.

Hyun, who contributed to the development of guidelines for organoid research five years ago, remarked on the swift evolution of the field. “We’ve gotten to the point rather quickly,” he stated, emphasizing the need for immediate protective measures for research animals involved in organoid experiments. As scientific exploration continues, establishing guidelines and regulatory frameworks will be essential to navigate the complexities of brain organoid research and address public concerns.

The Asilomar meeting served as a critical stepping stone for scientists eager to discuss the ethical dimensions of their work. As this innovative field advances, the balance between scientific exploration and ethical responsibility will remain a focal point for researchers and society alike.