How a Prison Book Program is Transforming Lives Behind Bars

Maria Montalvo’s eyes light up with emotion as she talks about her favorite authors. Her list includes Isabel Allende, Octavia Butler, Toni Morrison, Erika L. Sánchez, and John Grisham. “Reading makes you wiser and you learn how people live in other countries. It takes your mind to other places you can’t travel to,” she says. Montalvo is not your average reader; she is an inmate at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility in New Jersey, participating in the Freedom Reads program, which has been promoting literacy in U.S. prisons since 2020.

“Freedom Reads has brought books on different topics, and it’s very important to read because it makes you wiser,” Montalvo, 60, shared in an interview with Noticias Telemundo. “Books change the prison climate; they change the way people think about themselves. This opens your mind and makes you want to change.” The arrival of the books at her facility in May was a memorable event for Montalvo. “They brought two bookcases that are very symbolic and very important, because they relate to literature, justice and writers like Martin Luther King,” she said.

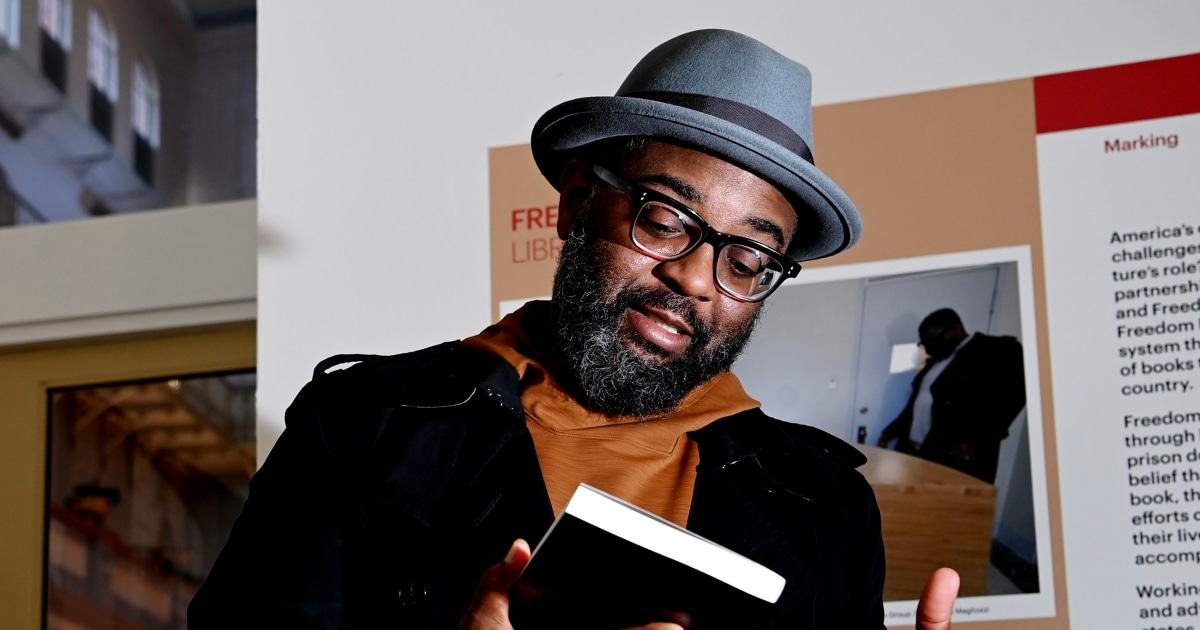

The Genesis of Freedom Reads

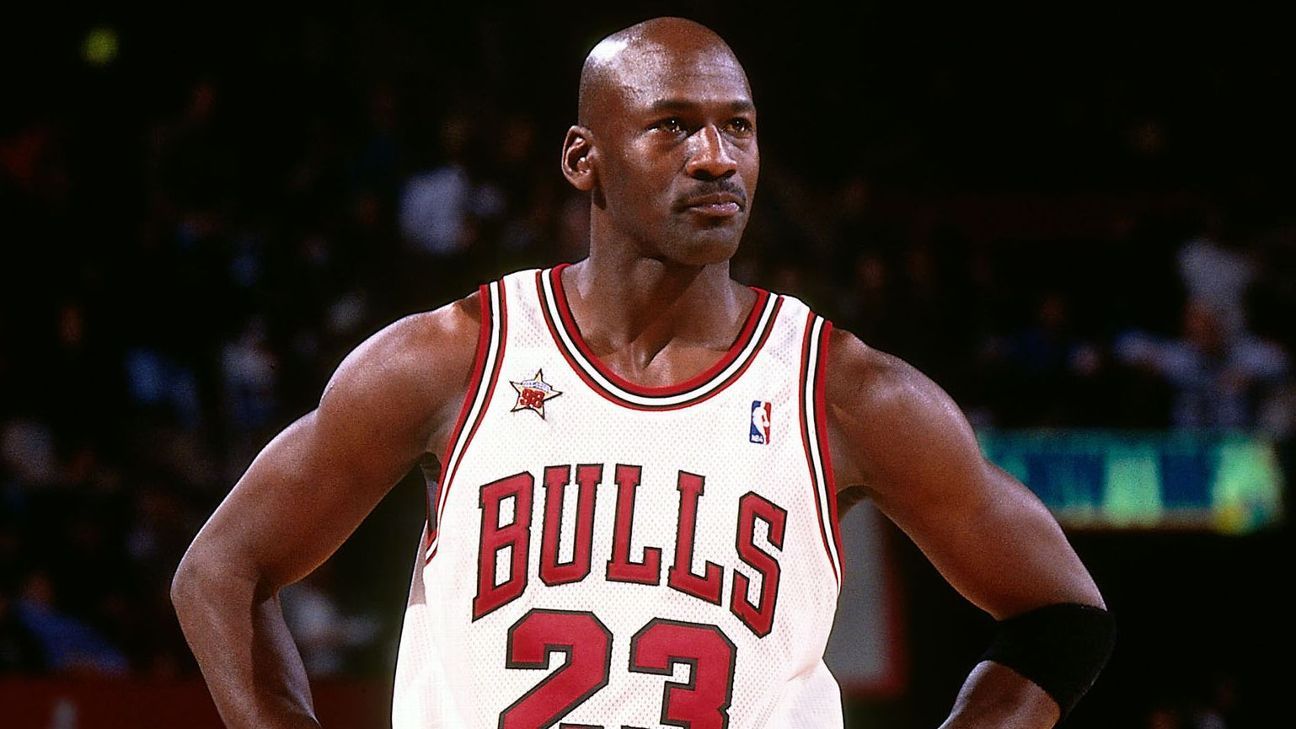

The origin of Freedom Reads is deeply connected to Reginald Dwayne Betts, who was sentenced to nine years in the Virginia prison system at the age of 16 for car theft. “In prison, I discovered books. I became a poet and also a very good communicator. I was able to make friendships and connections that have lasted decades. Books gave me an understanding of the world,” Betts explained in an interview with Noticias Telemundo. After his release, Betts earned a law degree from Yale University and became a published poet, receiving Guggenheim and MacArthur fellowships. In 2020, he co-founded Freedom Reads to expand access to books for inmates across the United States.

Betts noted the scarcity of reading materials in prisons, where libraries are often limited in both size and accessibility. “I asked myself, ‘What would a library be?’ And I decided it would be a collection of 500 books, and I called it the Library of Freedom, because I believe in the idea that freedom begins with a book.” Working with architects from Mass Design, Betts created uniquely designed libraries. These libraries are crafted from maple, walnut, or cherry wood and are intended to contrast with the harsh architecture of prisons.

Impact and Expansion

Freedom Reads has made significant strides, installing 498 libraries in 50 adult and youth prisons across the United States and placing approximately 280,000 books into the hands of inmates. Despite this progress, Betts acknowledges that much work remains. “We’ve probably reached less than 1%, maybe 0.5%, of the prisons in this country,” he said. “We’re not in any federal prisons yet. We’re only in 13 states, and we’re missing more than 30. So we have a lot of work ahead of us.”

Since 2023, the organization has also administered the Inside Literary Prize, judged by incarcerated individuals. The inaugural award went to Imani Perry’s book “South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation.” By 2025, the competition expanded to include more than 300 judges from 13 prisons, including Puerto Rico.

Challenges and Future Prospects

Finding reading material in prisons is not without its challenges. According to Betts, most facilities have only one library, open for limited hours and requiring a permit for access. The Federal Bureau of Prisons, while not providing specific data on literacy initiatives, stated through spokesperson Scott Taylor that it closely monitors programs like Freedom Reads. “Bilingual instructions and materials are provided in Spanish and English, supported by digital tools that offer accessible resources for those learning English,” Taylor noted.

Research by the Mackinac Public Policy Center found that prison-based reading and education programs reduce recidivism by 14.8% and increase employment prospects by 6.9%. “I love having conversations with people inside prisons,” said David Pérez, Freedom Reads’ library coordinator. “They read a lot, and it moves you when you see them crying because they’ve read a poem or a novel — it’s unique.”

Maria Montalvo, serving a life sentence for a crime committed in 1996, has dedicated her time to studying mass incarceration and engaging in reading circles. “There are many books in Spanish and English. So you can sit with many of the women who don’t speak English and read a book, but at the same time, another group is reading the same book in English, and you can have a conversation afterward,” she explained.

Freedom Reads continues to strive toward its ambitious goal of establishing libraries in 20,000 prisons. As the program expands, it not only provides access to literature but also offers inmates a sense of inclusion and a platform to express their voices. “It’s having a voice,” Montalvo said excitedly, reflecting on her participation in the literary prize jury. The impact of this program is a testament to the transformative power of books, even behind prison walls.