AI in Agriculture: Australian Farmers Skeptical of Tech Promises

Australian farms are at the forefront of a technological revolution that promises to transform agriculture. Over the past decade, more than US$200 billion (A$305 billion) has been invested globally in innovations such as pollination robots, smart soil sensors, and artificial intelligence (AI) systems designed to assist in decision-making. However, the farmers themselves remain skeptical about these advancements. Recent interviews with dozens of Australian farmers reveal a sophisticated understanding of their needs and a cautious approach towards the utopian promises of tech companies.

The announcement comes as the agricultural sector faces increasing pressure to adopt new technologies. Terms like “precision agriculture,” “smart farming,” and “agriculture 4.0” suggest a future where human, computing, and natural systems are intricately connected. Technologies like remote sensing, autonomous vehicles, and AI are expected to monitor and predict farm activities, from crop growth to cattle weight gain.

Farmers’ Perspectives on AI

Our research team conducted over 35 interviews with Australian livestock producers. The farmers’ responses highlighted two main themes: “shit in, shit out” and “more automation, less features.” The former, a variation of the computer science adage “garbage in, garbage out,” reflects concerns about the reliability of data used in AI models. Farmers are wary of technologies they do not fully understand, particularly if they are unsure of the data inputs.

Meanwhile, the phrase “more automation, less features” encapsulates farmers’ desire for straightforward, labor-saving technologies. In rural Australia, where human labor is scarce, machines have historically filled the gap. Innovations such as windmills, wire fences, and the iconic Australian sheepdog have long been integral to farming. These technologies, while not autonomous in the modern sense, offer simplicity and reliability, qualities that farmers value.

Historical Parallels: The Suzuki Sierra Stockman

One farmer recalled the impact of the Suzuki Sierra Stockman, a no-frills four-wheel-drive vehicle that became iconic on Australian farms in the late 20th century. “Once I learnt that I could actually draft cattle out with the Suzuki, that changed everything,” she said. This example illustrates how farmers have historically adapted existing technologies to meet their needs, often in ways the original developers never anticipated.

The combustion engine revolutionized 20th-century farming, and computers may play a similar role in the 21st. While computers are still largely confined to offices, their integration into farming is increasing. Sensors in water tanks, soil monitors, and in-paddock scales are becoming more common, providing data that AI systems can use to assist farmers.

The Future of AI in Agriculture

AI has the potential to become a beloved tool for farmers, but its path to widespread acceptance depends on how well it can be adapted to meet farmers’ needs. The technology must be simple, adaptable, and reliable to gain the same status as past innovations. As AI systems evolve, they must account for the practical realities of farming, rather than just the theoretical possibilities imagined by developers.

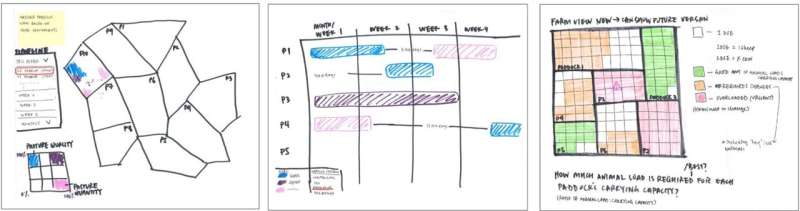

According to Thomas Lee and colleagues in their study “Unlocking digital twin planning for grazing industries with farmer-centred design,” the success of AI in agriculture hinges on a collaborative approach that incorporates farmers’ insights and experiences. This research, published in Agriculture and Human Values, underscores the importance of designing technology with the end-user in mind.

Thomas Lee et al, Unlocking digital twin planning for grazing industries with farmer-centred design, Agriculture and Human Values (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s10460-025-10752-x

As the agricultural sector continues to evolve, the integration of AI and other digital technologies will likely play a crucial role. However, the journey to full adoption will require ongoing dialogue between farmers and technology developers to ensure that innovations are both practical and beneficial. The lessons from past technological shifts suggest that the most successful innovations will be those that are adapted to fit the unique needs of the farming community.